On the Wild Side

Hunting in history's footsteps is a time honored and sacred tradition on the plantations of the Lowcountry.

It was about 4 a.m. when I heard Karl Sutka’s old Chevy rattling down our gravel driveway, piled high with hunting gear and all the fixin’s for a down-home country breakfast.

The embers were still glowing in our oversized stone fireplace from the night before when my husband, Cloide, went downstairs to greet him in the chill of the night. Pat Conroy used to comment on how he had such a delightful Southern name.

Together they unloaded the car and took the coolers to the small kitchen near the dining room. It was just a little larger than a broom closet, small because when the house was built in 1929, it was a party house once owned and built by New York stockbroker Arthur Barnwell. Back then all their food and supplies were cooked and brought over on boats from the mainland long before the McTeer Bridge existed, connecting Lady’s Island to the mainland. Folks around town used to tell stories about his parties, which lasted for weeks. He brought in the Ziegfield Folly girls and Esther Williams to swim in the massive pool. But that’s a story for another time.

Cloide threw some oak on the fire from a massive tree he and our neighbor General Tompkins had discovered in the woods along the edge of the property. Blown down many years ago, it now was aged just right. Once cut and split, its limbs were a perfect size for the brick fireplace in the living room, easily six feet across and five feet tall. Fat lighter from the heartwood of pine trees was the key to getting it ablaze in short order. Soon the dark pecky cypress, twenty-foot high walls in the living room, and wide ceiling beams began to warm up, and the crackling sound of burning wood was all that broke the silence of the night.

An invite to hunt at Pleasant Point Plantation was much cove†ed in Beaufort County, and few could gain entry to this distinguished inner circle. Judge Clyde Elstrop, Judge Martin, and Hilton Head developer Joe Fraser were amongst the fortunate. They were regulars. Grown men fought for an invitation when word spread about the large presence of marsh hens on the pond and the big breakfast served before the hunt.

Karl’s lighter-than-air biscuits rising in the oven and grits cooking in a black cast iron pot on chilly mornings were the talk of the town. Karl had a secret place, somewhere between Yemassee and Charleston where he bought the best sausage on the planet, but he never told a soul about it. To this day, it remains a long-kept secret.

Sporting traditions, conservation, and history are sacred on the plantations of South Carolina. Time-honored traditions far transcend the mere pulling the trigger. Out on the sea islands, lives are measured by the passage of hunting seasons and time outside with friends, guns, and good dogs.

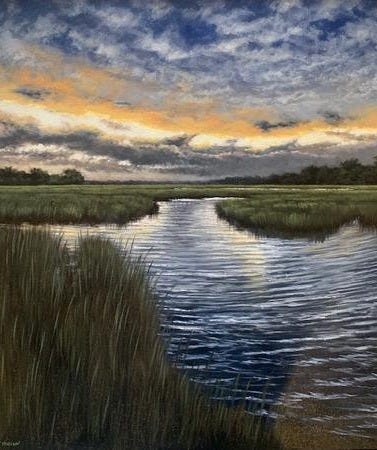

Standing out on the dock at daybreak in front of the house with no wind, a flood tide rising to the brim with only the tips of spartina canes showing above the water’s edge, I knew it was time for the arrival of marsh hens. The tide looked perfect for hunting marsh hens. The moon is full and the fall has brought flood tides which allow hunters to get back to where the marsh hens live.

I loved all of nature, this land, and each new moon. As autumn drifts in so do the marsh hens, birds of the tidal marshes of the Lowcountry, the great clapper rails, Rallus crepitans. Their migrations take place under the darkness of night, and in perfect silence; but the moment they arrive at their destination, they announce their presence by a continuation of loud cackling, meant as an expression of their joy.

In preparation for the hunt the next day, we went on a mission to find where they were. I remember casting off in a canoe at 4:30 a.m. on a low tide through what felt like an impenetrable jungle of marsh grass and little hummocks set here and there stretching out in front. In the great rush of full and new moon water, marsh hens will hunker in what little cover they can find. At low tide, you can hear them cackle but never see them.

“If you hunt them on a high tide or flood tide, that forces them out of their habitats,” said Cloide, “ and make sure to make the birds fly before taking a shot!” He told me there is no sport shooting at a sitting bird.

These birds cannot be shot from a boat under the power of either an outboard or a trolling motor. This adds to the challenge a bit, but the higher-than-average water levels make it easy to pole or paddle boats quietly through spartina grass. A canoe needs to be procured, and paddled by one or two experienced persons, the sportsman standing in the bow aiming his .410, and his friend in the stern who quietly stears the skiff. As we nosed the canoe into the scant cover, suddenly birds erupted from a floating rick of dead spartina cackling and flapping like pheasants.

Convinced the hunt the next day would be a good one, we paddled back to shore. By now dawn was breaking, and a snowy egret stood in silence on the bank while mud minnows darted about. I felt both mystery and magic that morning in this little corner of my world knowing tomorrow would be a perfect Lowcountry day of chasing marsh hens and making memories in the salt marshes of Beaufort County.

Though not reputed as fine table fare, marsh hens can be made good enough to brag about. Soak overnight in salt water, the second night in buttermilk, dredge them in seasoned flour, fry them up in hot oil until golden brown, and simmer in black pepper gravy until the meat falls off the bones. Serve over steamed rice or mashed potatoes. I always claimed to like them even if I didn’t think so. But eating a marsh hen is a certain right of passage.

I can see you and dad now! That house and pleasant point always fascinated me. It was a treasure to grow up and explore all these places.

I loved this story so much! I grew up on St. Simon’s Island in the 40’s and 50’s. My older brother was the hunter in the family and I got to eat many a marsh hen. I love them and really miss them. We now live on Harris Neck in McIntosh CO. GA, as SSI is just too different, not the place where I grew up. On the fall high tides I look out from our dock at the tiny tips of spartina and wish that

my brother were here to go hunting. He came back to live on SSI but is not able to go hunting them now. He did take us hunting a few times years ago. I was pretty rusty at shooting then but did get a couple of hens. I don't know anyone who hunts them here but would love to have some. Offer me a plate of doves, or quail, or a plate of clapper rails and it would be Marsh hens every time.

I enjoy reading your stories, thank you!

Sissy Lingle